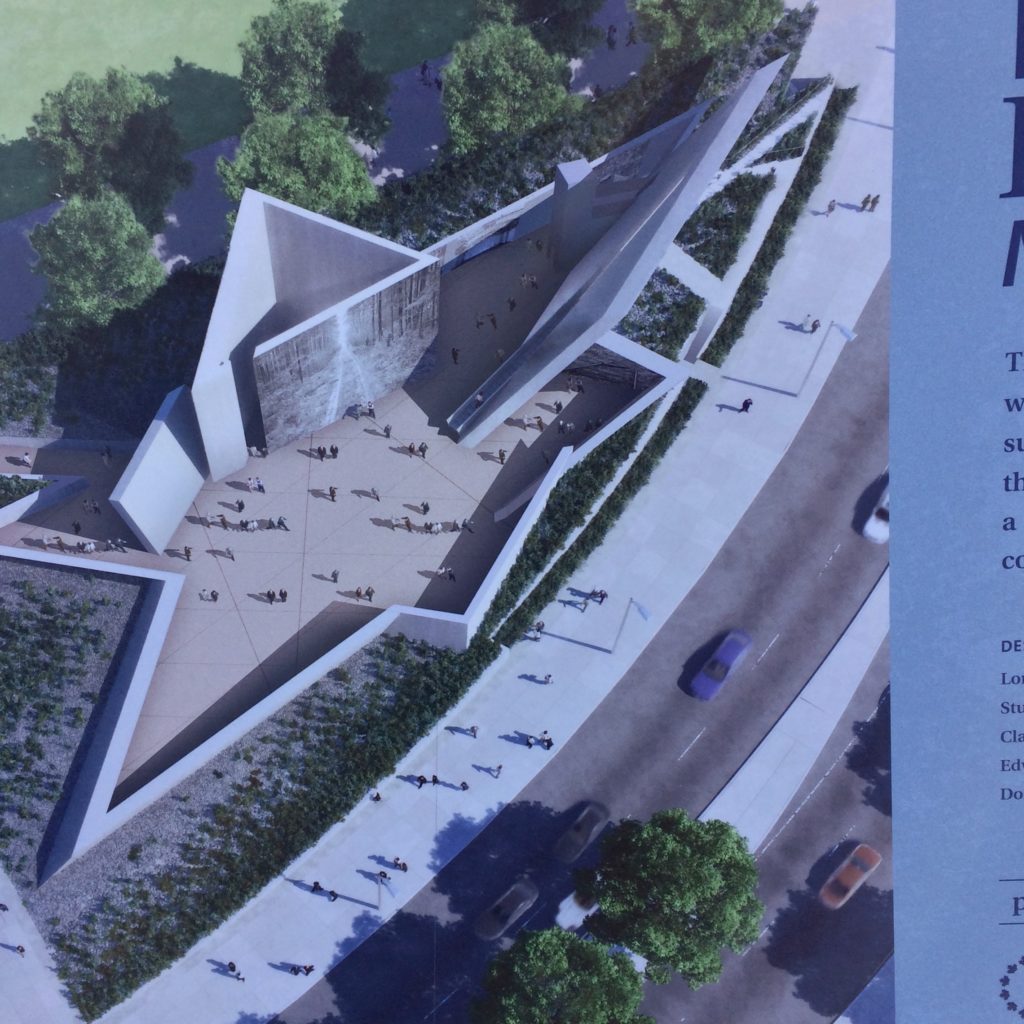

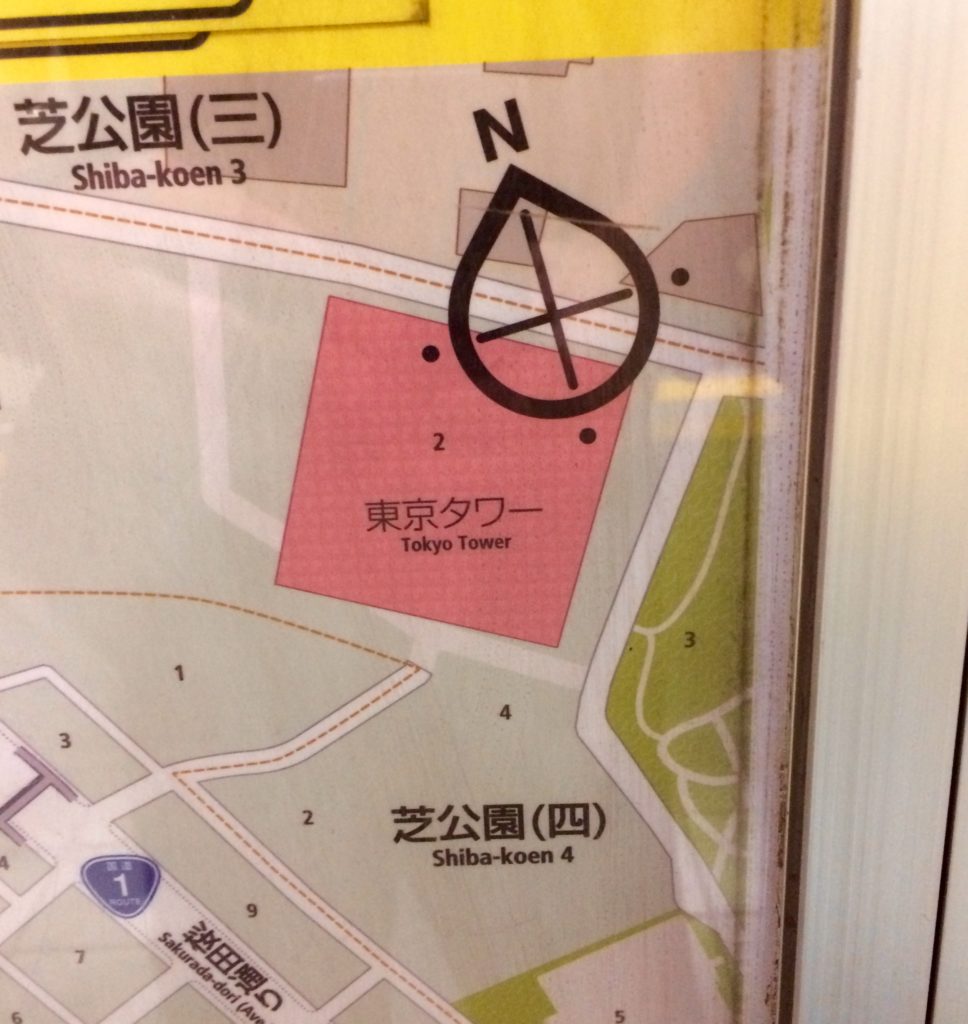

The image above is from a student ideas competition 25 years ago. The thematic link here is simply to ‘the idea of a tower’. The top photo is the Tokyo Tower taken from the balconcy of an AirBnB in 2016 .

Notes on Architecture 9 – tower-tower – A Student Project

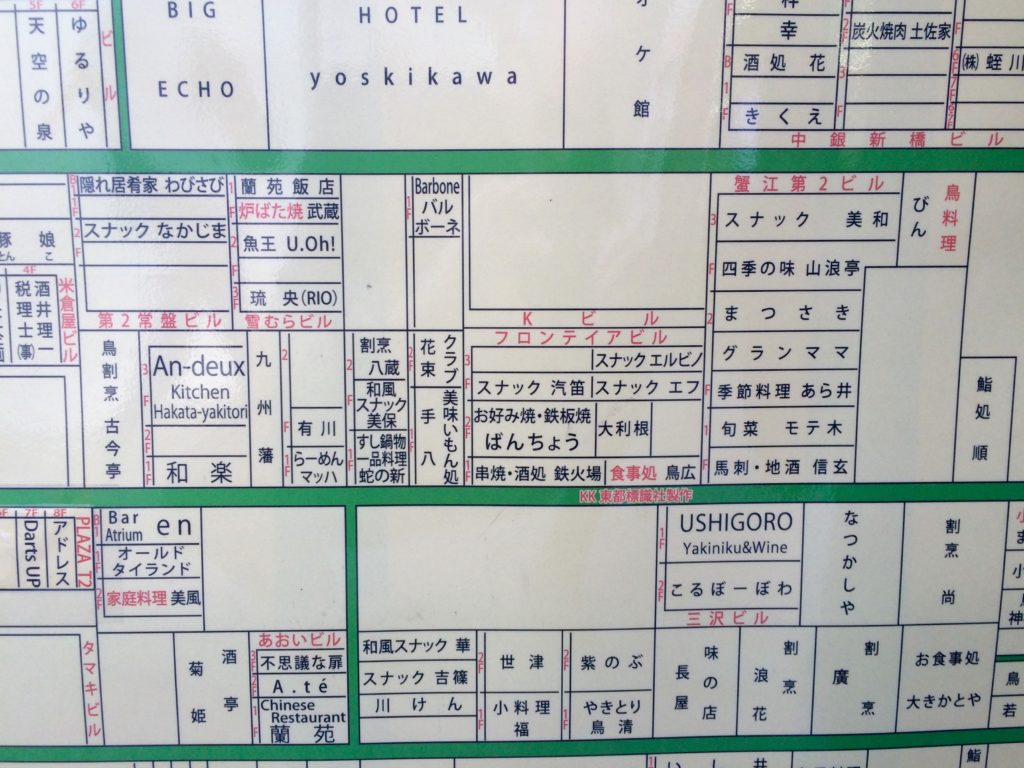

While a student in a masters program in Tokyo in the early 1990’s, I completed several entries to architectural competitions. During first year, submissions were primarily to competitions sponsored by japanese architectural publications, where most participants were university students. Redeveloping the Tokyo Tower was the challenge of one of these. The Tokyo Tower is a heavy steel, loose version of the Eiffel Tower. It was completed in 1958, and is the second tallest structure in Japan according to Wikipedia. It has none of the detailed, lace-like sophistication of the original french tower, in favour of a robust simple approach. It is a designed product of it’s time. While the shape is unmistakably that of Eiffel’s, this prototype is mid-century japanese engineered modernism. The tower’s design is credited to Tachū Naitō (内藤 多仲) 1886 -1970, a Japanese architect and engineer, who started his career studying navel engineering. Nikken Sekkei, a major engineering and architectural services conglomerate, was also involved. The Tokyo Tower remains popular with Japanese broadly, however at the time of the competition in 1992, I would think it may have appeared clunky to designers. In copying the french form so closely, it was minimally unoriginal. In any case, at least some individuals at the time of the competition, thought it interesting or worthwhile to have students look at options to revisit the tower.

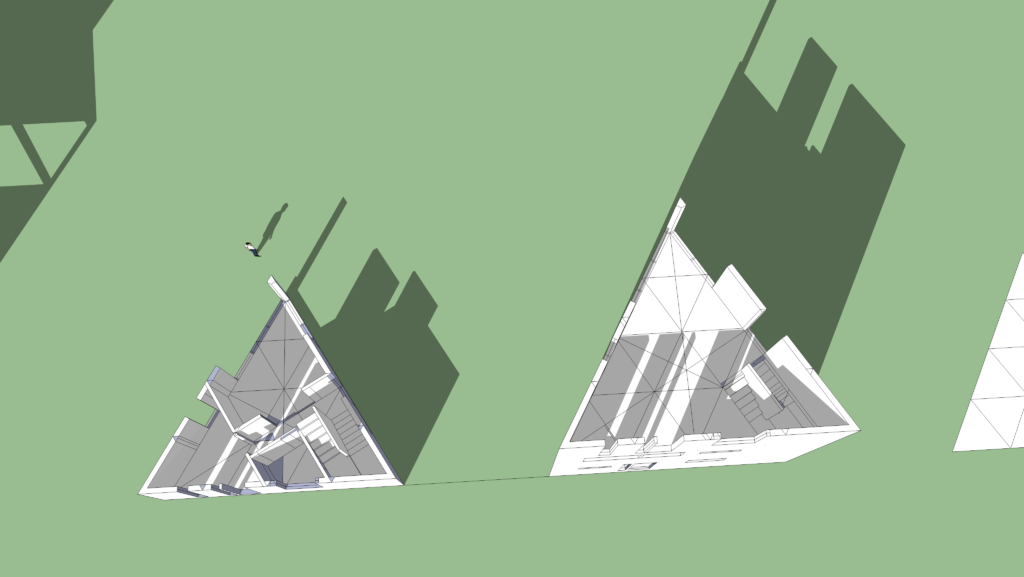

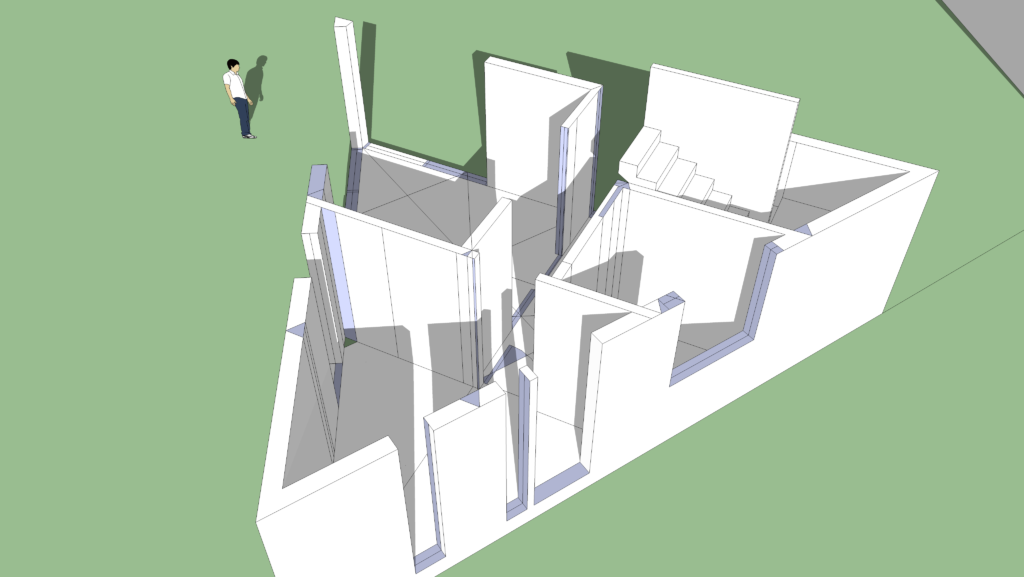

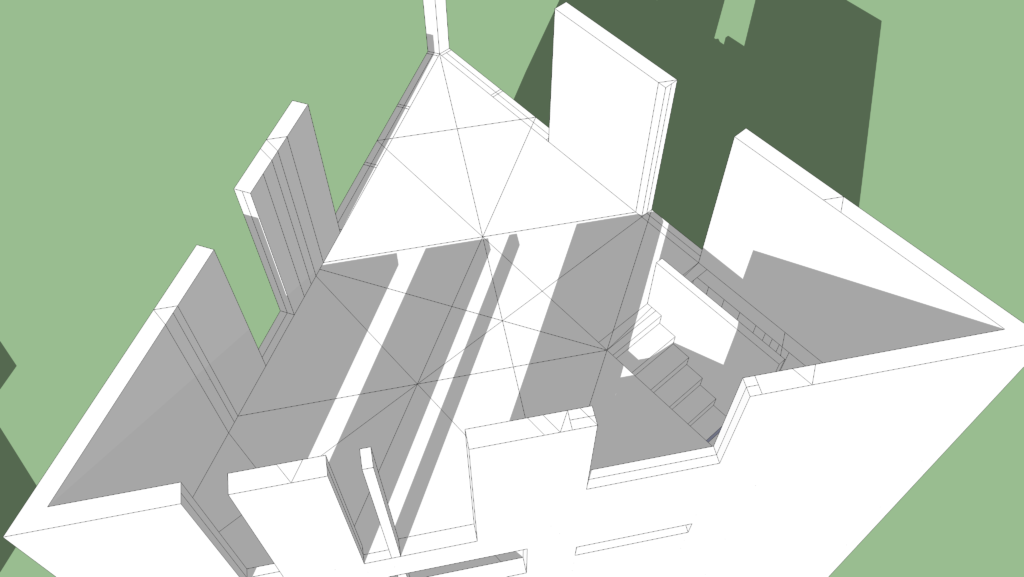

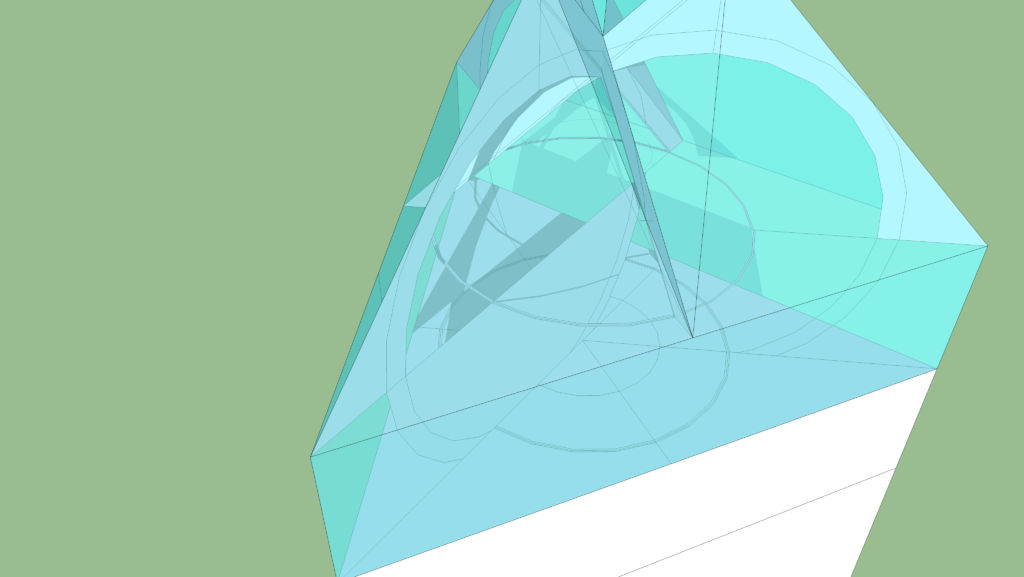

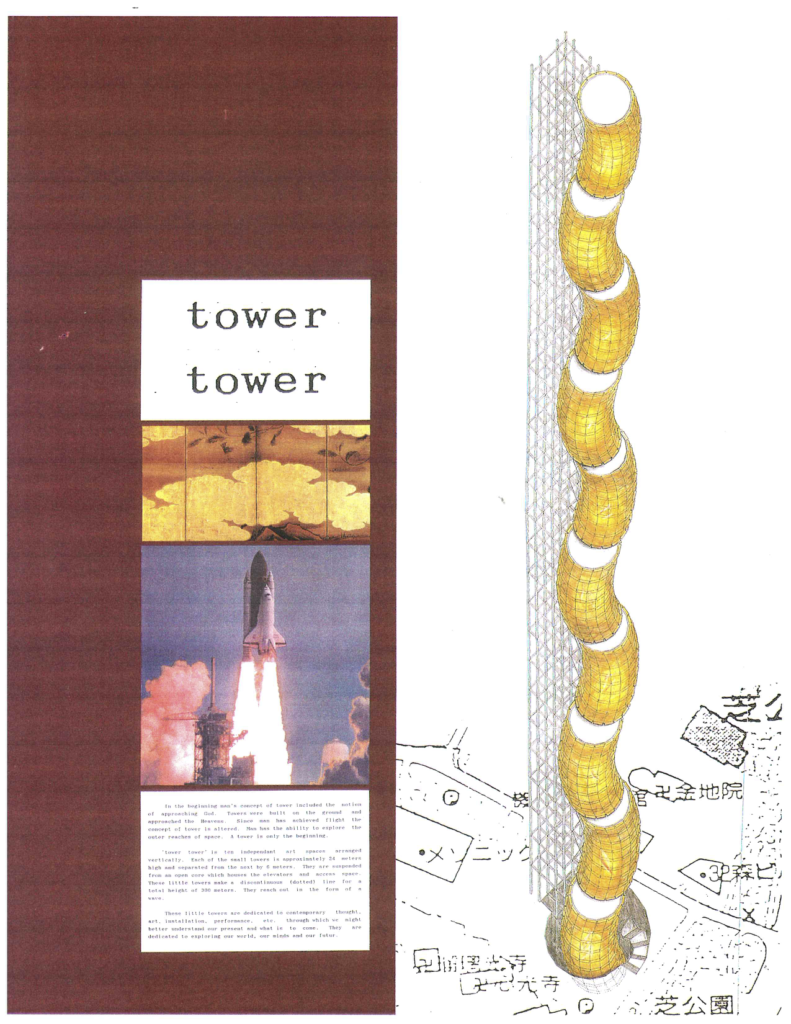

Broadcasting and tourism were key programme elements of the existing structure. The proposal here, ‘tower-tower’, consisted of a simple open steel frame that would contain elevators, stairs and services. Cantilevered off the main open structure, that was intended to be as light as possible, were a series of ten large, fat macaroni-like volumes. These were unconnected to each other. Inside the large curved pieces, exhibitions, event spaces, bars, restaurants, and viewing platforms could be located. A wavy dotted line pointing up was created by the unconnected little towers. The project was hand drawn and developed in an axonometric view by shifting faceted rings upwards on an arc. The form partially came out of an earlier student project for a small building in suburban Tokyo. That programme was for offices for a local steel manufacturer. A round, steel faced building, 6 stories high was developed with a facade that had some level of panelization, and three-dimensional articulation. The exercise was proposed by a professor who was in fact working on a real commission – a small suburban Tokyo office building, for a steel manufacturer.

At the time I was interested in colour field painters, Louis Kahn and contemporary french, english and japanese modernists like Jean Nouvel, Foster+Partners and Fumihiko Maki. The aesthetic lessons for the tower-tower project came from these, as well as earlier studies, including the steel office building – but also from developing work by fellow students, artist friends and teachers. These are, then as now, all important factors that together through trial and error, intertwine and contribute to form a design language – a framework which potentially may communicate something with rigour and consistency.

The explanatory text that accompanied the tower-tower submission, was purposefully written in simplistic english. This was based on previously published winning japanese student entries, that I had looked at. Submission texts that appeared with published entries were often in english, with varying levels of brokenness, and many a poetic line. Loosely copying this, the text for tower-tower was an affectation, partly in an effort to find the right tone, language and expression, that might have resonance with those in the japanese architectural community who were the judges. In the case of this exercise however, the communication strategy, along with the design, were not differentiators.